The Governor, the Commandant, the Commissioner, the Minister for the Colonies and a convict forger colluded in the extrusion of Christ Church’s superstructure to attract investment and immigrants to the newly free settlement of Newcastle. Historian Sue Rabbitt Roff with a story for the ages.

It’s a story with many of the hallmarks of ‘modern’ real estate rorts, including illicit tenement grants, fake surveys, and dubious marketing. And it all started with Governor Lachlan Macquarie promoting the value of his land in the Hunter Region.

In his 11 years as Governor of New South Wales from 1810, Governor Macquarie spent more time in Van Diemen’s Land 800 miles from Sydney than in the penal colony of Coal River, less than 80 miles away that became the town of Newcastle in the 1820s.

Coal River was populated by recidivist convicts who had been banished from Sydney. From 1816 through 1818, it was under the authority of Captain James Wallis as Commandant, who used the convict population to build a church on the hill overlooking the hamlet.

It came into use in December 1817, and Governor Macquarie officially opened it in August 1818, noting in his Journal that “the Congregation on this occasion consisted of between 5 and 600 persons”.

Sunday church services were used to muster the convicts from various points around the settlement. Since the building covered an area about the size of a tennis court it would have been a crush, even if they were all standing. Some were sent up to the 80ft gallery, which would have been rather hot.

The land grant

When Wallis resigned and left for Home in 1819, Governor Macquarie recommended him for a large land grant explicitly in anticipation that free settlement would be permitted in the early 1820s, as it was.

But even as the hamlet was being transformed into a town, the jerry-built church on the hill was falling down. The superstructure of the tower, steeple and spire had to be reduced because the foundations were built as much upon sand as on rock and could not support their weight.

People became too frightened to go to services inside the church.

In 1819, J T Bigge was appointed a special commissioner to examine the government of New South Wales. He took evidence about the increasing debilitation of the church in Newcastle – which had had to be ‘re-ceilinged’. But while he was very critical in his Report of the ‘ostentatious’ building that Macquarie had encouraged in Sydney and elsewhere he didn’t include Christ Church Newcastle among the offenders.

Although serious charges were being levied at Macquarie from complaints made to his superiors in London, including references to Christ Church, they were not included in the information submitted to Parliament as late as 1828. This suggests that Bigge and the London-based colonial ministers were unwilling to admit that Newcastle was not yet ready for free settlement or investment.

A forged prospectus

A picture is often worth more than a thousand words. And there are images readily accessible that show the progressive reduction of the superstructure of the newly built Christ Church on the hill overlooking the hamlet.

But there is also a score of images that show images of a much-heightened tower, steeple and spire that began circulating in London in the 1820s, presumably in support of the hamlet that was trying to become a town in order to attract settlers and investment.

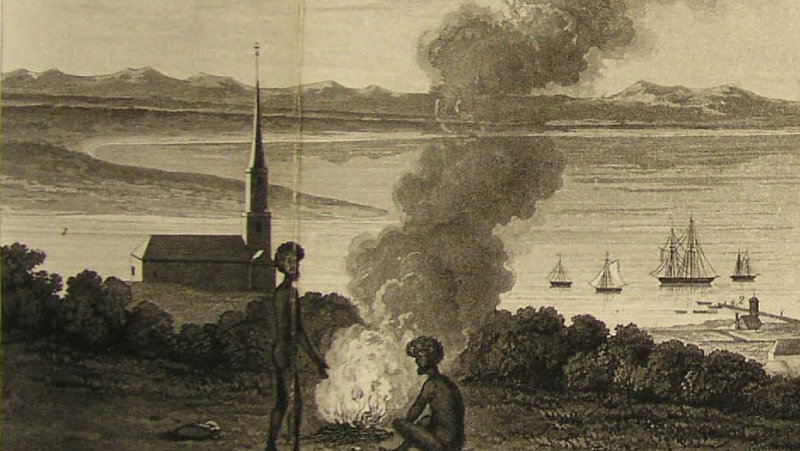

Joseph Lycett 1818 (Flickr)

It was rather like Pinnochio’s nose – growing with every lie told.

Enter Joseph Lycett. Governor Macquarie had granted Lycett, a recidivist forger, an absolute pardon on 28 November 1821; he left NSW in September 1822. Lycett cut his throat and died in England in February 1828. He had been arrested yet again for forgery and may have feared execution this time.

Lycett’s first known painting to include the church is probably from Newcastle looking towards Prospect Hill, dated circa 1818. The proportion of the body and roof of the church to the towers, steeple, spire and cross is about 1:1.

We know from evidence, including sketch plans presented to the Bigge Inquiry in January 1820, that the body and roof were about 45 feet high, and the height to the top of the Cross from the ground was 100 feet. The serried rows of houses at the foot of Prospect Hill have chimneys much the same size as the superstructure of the church above them.

But in the several subsequent depictions of Christ Church by Lycett that began to circulate in Britain in the 1820s the superstructure is progressively elongated to suggest a much more substantial church existed in what was now the free settlement of Newcastle.

Lycett prepared a collection of Views in Australia, or New South Wales and Van Dieman’s Land Delineated in Fifty Views that was ‘Dedicated by permission, to the Right Honble Earl Bathurst’ who was Minister for the Colonies from 1812 to 1827.

Joe Lycett (section)

Published in London in 1825 with said endorsement, it included images of Newcastle’s Christ Church with an imposing superstructure overlooking the nascent – very nascent – town of Newcastle.

The year 1825 was when the actual superstructure was being radically dismantled, a year after Governor Macquarie had died. Lycett’s Inner View of Newcastle (dated 1818 by Newcastle Art Gallery) is virtually the same composition in oils.

The proportion of body and roof to superstructure is nearly 1:3.

In 1821, Captain Wallis published a historical account of the colony of New South Wales and its dependent settlements.

It is widely thought that Joseph Lycett collaborated in this project. There are sketches and an engraving of Christ Church Newcastle that depict its superstructure as at least twice the height of the building above the roof.

Edward Close painting

Edward Close circa 1820

While Lycett and Wallis were both self-taught artists, it is even more surprising to find that Edward Close, a trained engineer sent to Newcastle to supervise the construction authorised by Macquarie, produced several ‘extruded’ images of Christ Church which were out of proportion with the other buildings in his townscapes.

His version of Christ Church featured on the front page of the catalogue of A State Library of NSW & Newcastle Art Gallery partnership exhibition in 2013 about Treasures of Newcastle from the Macquarie Period.

When Close left the Army in 1822, he was granted 2560 acres in the vicinity of Morpeth.

William Dangar surveyor

But the most startling image is the frontispiece of A Complete Emigrant’s Guide by H. Dangar, a second assistant surveyor in 1828.

The superstructure that had been radically lowered three years earlier is shown as five times higher than the body of the church from its roof. Dangar did, however, note that “latterly divine service has not been performed [in Christ Church] in consequence of the steeple having been considered unsafe.”

Emigration Guide 1828

Dangar’s image is in stark contrast to images of the Newcastle church in the field notes of Sir Thomas Mitchell, Surveyor-General of New South Wales, from 1822 until his death in 1855.

The Australian (not the Murdoch version) reported on the dismantling of the majority of the superstructure in May 1825.

The Macquarie prospectus

This review of the primary documents and images of Christ Church Newcastle may also be a key to the provenance of the Macquarie and Dixons Collector’s Chests, now held by State Library of New South Wales.

In his last tour out of Sydney, before he returned to Britain in early 1822, Governor Macquarie collected specimens of cedar and rosewood, which were thought to have commercial prospects back in Europe. He noted that his young son Lachlan and Mrs Macquarie had been present with stuffed birds and live animals from the Hunters River.

There were woodworkers and furniture makers in Sydney who may have made what has come to be known as the Collectors’ Chests, and it may well have been Macquarie himself who had them prepared as showpieces – or real estate prospectuses.

Images from Macquarie’s Collectors Chest showing Christ Church

It is known that the chests reached London and Scotland. But they were never displayed by Governor Macquarie despite the intense criticism he was fighting off for his building projects in New South Wales. Both chests have several depictions of Christ Church Newcastle on their lids.

It could be that some of the paintings on the chests had become an embarrassment to Macquarie because – like other images circulating in London in the 1820s,

they exaggerated the extent to which Newcastle had become a town ready for free settlement rather than an internal penal colony for recidivists from Sydney.

By the time Macquarie returned to England in mid-1822, news might well have been reaching home that the painters and engravers – and some of the surveyors – were exaggerating the grandeur of Christ Church in order to suggest not only a higher superstructure but also a higher level of development of the penal colony 80 miles out of Sydney that was being marketed as an investment opportunity for free settlers and their backers.

Rather than being displayed as a sort of real estate prospectus to attract free settlers to the colony. The Macquarie’s Collectors Chest at least was given to his best friend’s wife, the Right Hon. Lady Murray, at Strathallan Castle 400 miles from London – and 30 miles from my humble writer’s den.

Cockups and coverups revealed. UK Government failed Australian nuclear test veterans

Sue Rabbitt Roff studied and taught at Melbourne and Monash Universities. Her recent writings on cultural aspects of settler colonial Australia have been published in Meanjin, Overland, the Conversation, the Independent and on Pearls & Irritations. She is currently writing a revisionist history of British atomic tests and nuclear trials in Australia.