MANILA, Philippines—Almost 143 kilometers from the coast of Zambales, China’s “monster ship” got so close to the Philippine land mass that the government had to make its stand clearer: “We do not waver or cower in the face of intimidation.”

Jonathan Malaya, assistant director general of the National Security Council, said “we do not and will not dignify these scare tactics by backing down” as he stressed how China has been “pushing the Philippines to the wall.”

The 12,000-ton China Coast Guard (CCG) 5901, which is 165 meters in length, is China’s monster ship and the world’s largest that was seen off Capones Island on Jan. 4 and replaced by CCG 3103.

READ: PCG: As ‘monster’ sails away, another China ship nears Zambales coast

However, as the Philippine Coast Guard’s (PCG) BRP Teresa Magbanua “gradually pushed it away,” the “monster ship” came back on Jan. 11 “to outmaneuver” the PCG vessel, which is only 97 meters in length.

Article continues after this advertisement

READ: China’s ‘Monster’ coast guard ship back in WPS

Article continues after this advertisement

CCG 5901’s presence inside the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of the Philippines prompted the government to point out that it is now “contemplating things it was not contemplating before.”

“All options are on the table,” said Malaya, who stressed that the proximity of CCG 5901 is escalating tension between the Philippines and China over areas of the South China Sea.

RELATED STORY: China’s ‘monster ship’ keeps ignoring PH call to leave WPS

Renato de Castro, a professor of international studies at the De La Salle University, said the Philippines has to protest the presence of the monster ship in the West Philippine Sea.

But while it won’t be enough to stop China, he told INQUIRER.net that filing a diplomatic protest would express the Philippines’ strong opposition against China’s intimidation.

“It is not enough but really necessary,” he said. “It is an indication that we do not accept the situation, which we could not control, but nevertheless, we do not want the situation.”

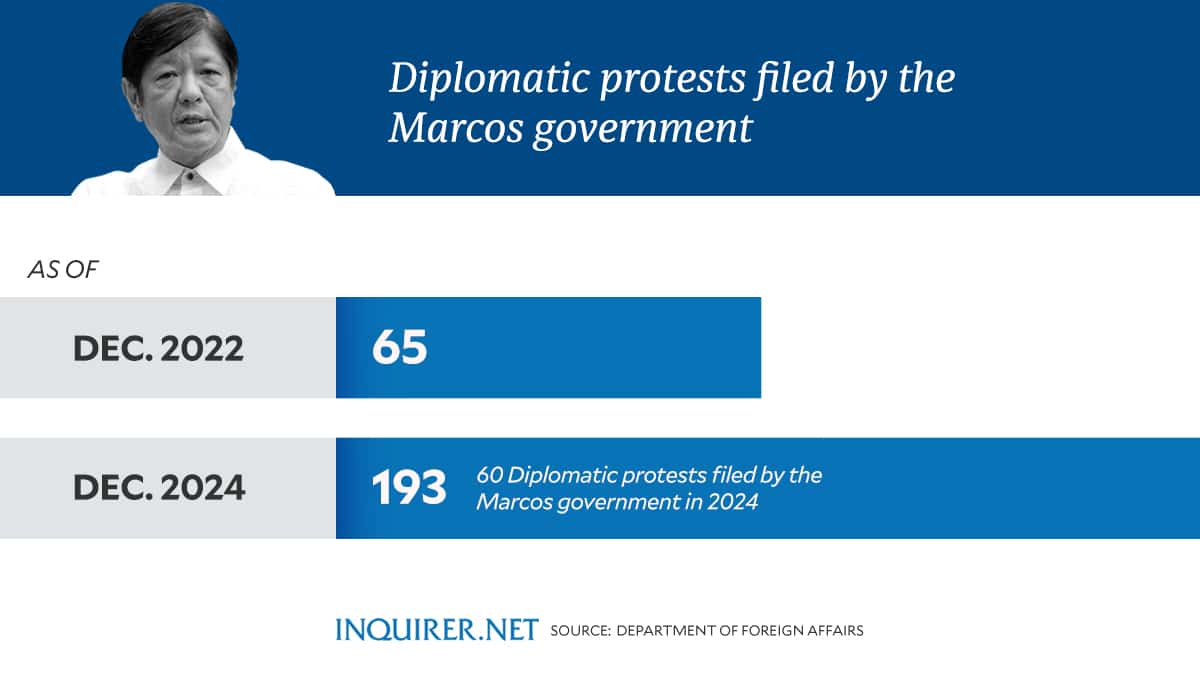

The government, since the start of the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in July 2022, has already filed close to 200 diplomatic protests against China’s aggression inside the EEZ of the Philippines.

Intimidating PH

Executive Secretary Lucas Bersamin pointed out that the presence of China’s monster ship could be a case of power projection, saying that Malacañang “view[s] it with concern.”

READ: West PH Sea: China ‘monster ship’ near Zambales ‘grave concern’ – Palace

In 2023, CCG 5901 was also seen off the coast of the state of Sarawak in Malaysian Borneo, close to the Kasawari Gas Development Project, based on a satellite image and AIS data from the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

This drew a response from the Royal Malaysian Navy.

De Castro had told radio station dzBB that China is really making it appear that they can conduct “intrusive patrols” and that the Philippines is helpless even if CCG vessels are already inside the country’s EEZ.

READ: China Coast Guard ‘Monster’ back at Panatag

SeaLight’s Gaute Friis, a defense innovation scholar at Stanford University’s Gordian Knot Center, said intrusive patrol would describe the presence of CCG vessels “within the EEZs of other states.”

“These patrols are a key component of China’s strategy to reinforce its expansive maritime claims in disputed waters [as it] aims to establish a continuous presence and gradually normalize its maritime activities in these areas,” he said.

Last year, CCG 5901 was also seen close to Ayungin, or Second Thomas Shoal, where the Philippines has grounded its warship BRP Sierra Madre to serve as an outpost in the West Philippine Sea.

Backing PH protests

Now, as diplomatic protests won’t be enough to really stop China’s aggression, De Castro said “we have to rely on our alliance[s],” considering the insufficient naval capabilities of the Philippines.

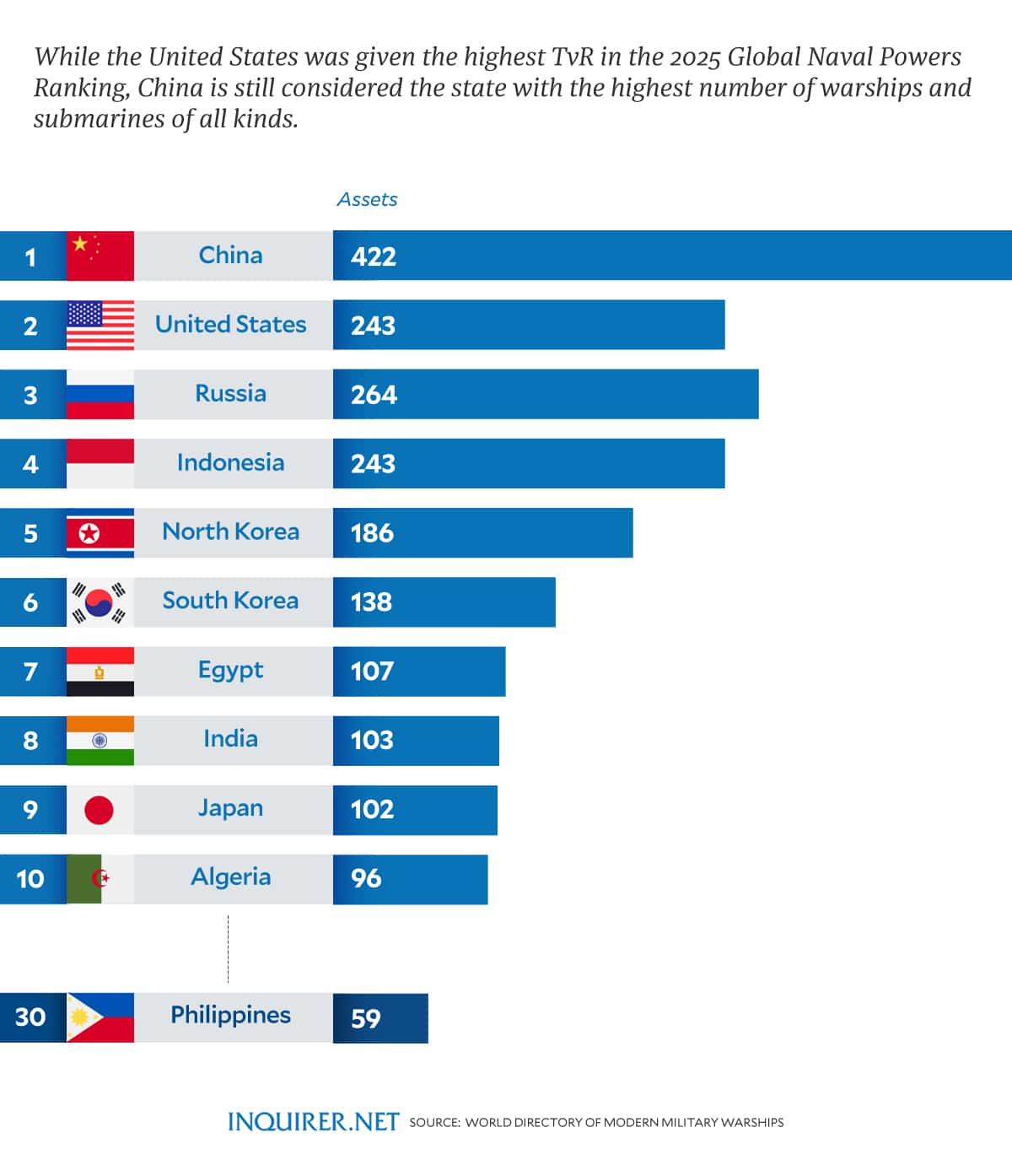

Based on data from the World Directory of Modern Military Warships, the Philippine Navy has a TvR of only 33.7 in the 2025 Global Naval Powers Ranking, which takes into account values related to the overall fighting strength of naval services in the world.

The TvR, or “TrueValueRating,” considers modernization, logistical support, attack and defense capabilities to assess strength not only based on the number of warships and submarines but rather on the “quality and general mix of the inventory.”

China’s People Liberation Army Navy has a TvR of 319.8, while the United States Navy, which is still considered as the world’s most powerful, was given a TvR of 323.9, although China has over 400 warships, compared to the 243 that the United States has.

Last year, however, Philippine Navy spokesperson Rear Admiral Roy Vincent Trinidad said “with what is happening right now, not only in the maritime domain but also in the air space, we are good with what we have.”

READ: PH defense assets sufficient amid China’s harassment in WPS – Navy spox

He said even with the present capabilities of the Philippine Air Force, Philippine Navy, and the Philippine Army, “we are good with what we have, and given more, they can perform even better.”

‘Hard’ executive decision

But engaging in the use of force is a “hard executive decision” that Marcos will have to make if the aggression of China would persist and intensify in the West Philippine Sea.

This, as De Castro pointed out that the possible use of force would bring the Philippines to the “realm of uncertainty”—will China be deterred or the Philippines will simply be caught in the middle?

“It will also depend on whether it is in the interest of our allies to really back us,” he said, stressing that once the United States or Japan assist the Philippines, China would really react.

He explained that “China cannot afford to lose force if it is confronted by the United States and Japan, and once we do it, once we put them in a situation where they would confront each other then we lose control of the situation.”

“Either we would be caught in the middle or our allies would simply abandon us. So it is an executive decision. The President has to take a calculated risk,” De Castro said, although stressing that the United States is expected to “act more decisively.”

He said: “So that is why you have to interpret or look at the Mutual Defense Treaty not in terms of its legalistic provision, but in terms of the political context when you have to make that decision.”

For comprehensive coverage, in-depth analysis, visit our special page for West Philippine Sea updates. Stay informed with articles, videos, and expert opinions.