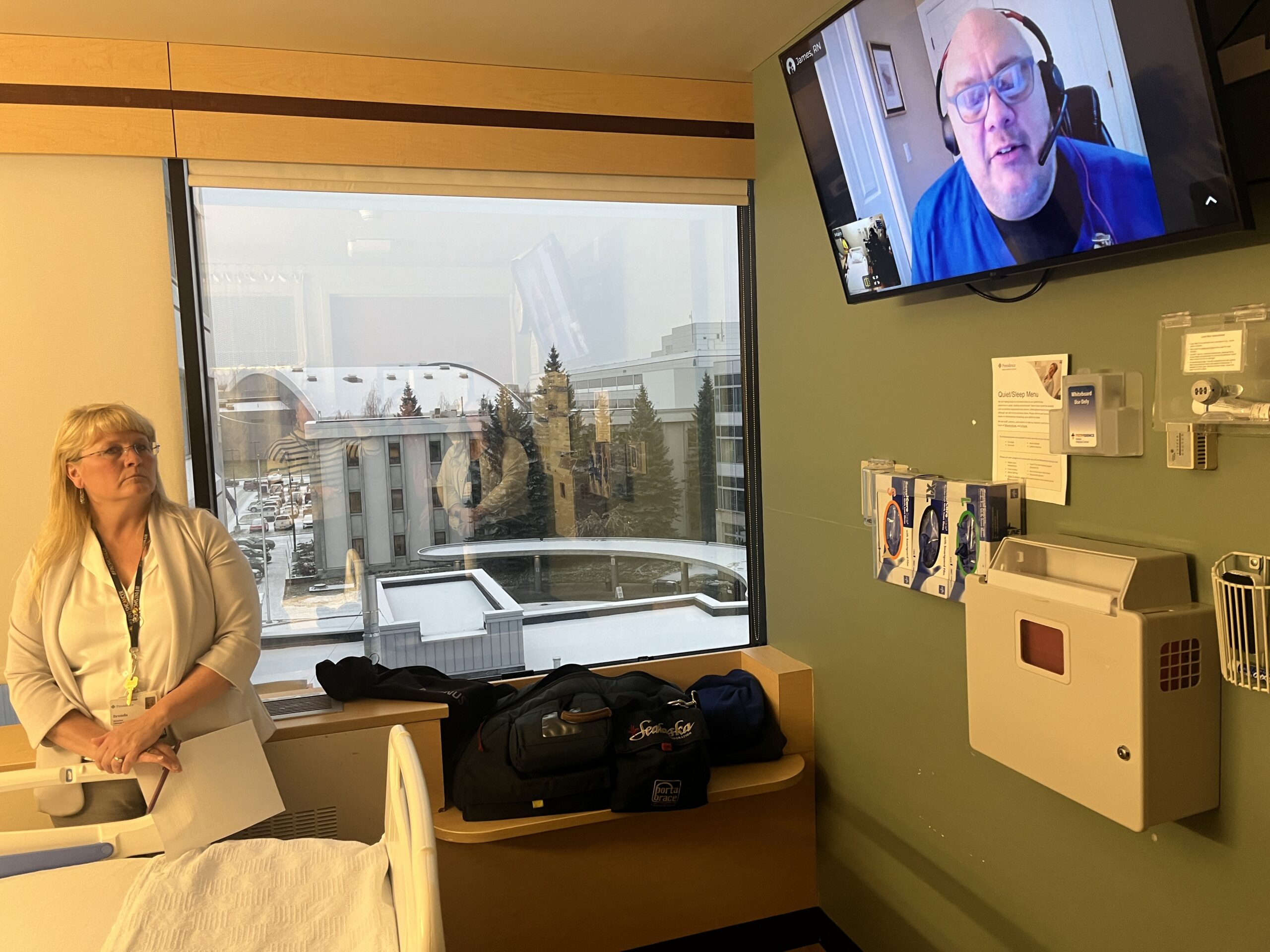

Nurse James Efird appeared on a wall-mounted screen that sat facing an empty white hospital bed. He was demonstrating technology installed for a new hybrid telenurse and bedside nurse program.

“When we chime in, the patient has the ability to accept or decline,” Efird said. “Then we also do a scan around the patient’s room [to] make sure the patient’s room is safe.”

He slowly panned a spherical camera mounted on the wall to “look” at different parts of the small hospital room.

“I’ve had patients say they look forward to me visiting again, and I spend as much time as they need and time allows,” Efird said.

Providence Alaska recently introduced a new system where telenurses work alongside bedside nurses in two of its units, and Efird is one of 17 telenurses hired for the work. He and the other telenurses do tasks like discharge planning, medication management and patient education, tasks representatives from Providence say often don’t require in-person care. For each patient, Efird collaborates with the patient’s bedside nurse.

The system is one way Providence Alaska is working to address the state’s nursing shortage, which like much of the country, is projected to worsen in the coming decades. Alaska is expected to have a shortage of about 5000 nurses by 2030, according to data from the Bureau of Health Workforce.

Brenda Franz, a director of nursing at Providence, said she’s hopeful the system will help alleviate the shortage.

“It’s very difficult to recruit nurses to Alaska,” Franz said. “Our geography, we’re remote, moving here is difficult. You have to leave all your family, unless you have family that are here.”

Jordan Thompson, a nurse manager on a unit that started using the system about three weeks ago, said there were almost 10 applicants for each position.

“I think it’s very sought after because it’s still clinical,” Thompson said. “It’s still in the hospital, [where] a lot of people want to be, but it’s without physically being at the bedside. So it’s kind of the best of both worlds.”

She said bedside nursing can be exhausting, so some people close to retirement or already retired applied. She added that few virtual positions available to nurses still let them work directly with patients, which is a plus for many.

Aside from being desirable, telenursing positions are flexible. While many nurses in this crop of hires live in Alaska, the position only requires that someone have an Alaska nursing license. And in the future, if Alaska joins a reciprocal licensing agreement, filling these positions could be even easier.

Thompson said this program won’t reduce staff hours on the unit overall, but she’s convinced systems like this increase patient outcomes and satisfaction.

“Other hospitals that have moved forward with virtual nursing have really raised their patient satisfaction scores, and so they have less pressure injuries, less hospital infection,” Thompson said.

Most hospitals across the country use some kind of telemedicine technology, and several are testing out similar systems. Providence piloted this program in 2021 and it’s now used in seven units across their system of hospitals. A representative from Providence said they don’t have much data on patient and staff outcomes for this program, but early data suggests it may help reduce staff turnover and may reduce the likelihood of falls and a type of urinary tract infection for patients.

But this move to integrate telenurses isn’t sitting well with many Providence Alaska nurses. Madison Eckhardt, a registered nurse at Providence in a step down unit from Intensive Care, is worried about relying on telenurses because she said many patients in her unit need to be watched carefully.

“It’s not an overstatement for me to say that even our simplest patients are at risk of bleeding out in minutes,” Eckhardt said.

Providence has tested this system, including implementing it in one unit like Eckhardt’s starting in March of 2024. But Eckhardt said telenursing is not appropriate for about half of the patients in her unit.

“They’re delirious, they’re confused, they have dementia, they have visual or hearing impairments, or they just plainly do not want to have anything to do with a camera on them,” Eckhardt said.

In response to these concerns, a Providence spokesperson wrote that “patient safety is not being compromised.”

But Eckhardt said nursing is a profession that requires hands-on work, and she’s worried about taking on an additional bedside patient. Now, she said, each nurse is in charge of four patients, but they’ll soon be in charge of five, ostensibly because the telenurse is taking enough of their duties to significantly reduce their workload. But Eckhardt said the new system hasn’t reduced their work enough during these first three weeks to justify adding an extra patient.

“The virtual nurse was going to offload a vast portion of our work that would allow us then to accommodate a fifth patient, but we’re not seeing that,” Eckhardt said.

Eckhardt said she’s personally talked to all of the 70 nurses in her unit and over a dozen have started to look for new jobs.

Because of the changes to the number of patients a bedside nurse will oversee, the union that represents Providence Alaska nurses, the Providence Registered Nurses Bargaining Unit, filed an unfair labor practice charge against the hospital on Oct. 30.

The union’s president, Tara Colegrove, said it represents a significant change in working conditions and Providence didn’t respond sufficiently to requests to bargain. Colegrove said the National Labor Relations Board will start investigating the charge in as little as a week from filing.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that this care model had not been tested in a step down unit of a Providence hospital.