This story was published with the Philadelphia Journalism Collaborative, a coalition of more than 25 local newsrooms, including Technical.ly, doing solutions reporting on things that affect daily life where the problem and symptoms are obvious, but what’s driving them isn’t. Follow at @PHLJournoCollab.

Whether it’s paying a bill or applying for a job, many everyday tasks exist almost entirely online — but not everyone has the skills or devices to access them.

Local governments and other orgs have implemented a new approach to bridge that gap: the digital navigator model.

The City of Philadelphia’s digital navigator program connects residents with community groups that can help them with technology challenges and digital resources like affordable internet options, devices and digital skills classes. Through trusted community partners, the city has built a network of navigators, and it’s been fruitful.

“I see it as a missing piece that really supports the rest of the ecosystem and the rest of the activities,” said Kate Rivera, executive director of the advocacy organization Technology Learning Collaborative (TLC). “It makes it so that people can access what they need and that they have the support they need to accomplish their goals.”

As progress inches forward, advocates in the digital equity space agree that navigators play a crucial role in improving access in daily life. Others question if the model is a temporary band-aid, pushing off larger systemic change.

The people behind the program say two things can be true at once. Individualized digital equity progress can happen alongside the crawl toward bigger fixes, according to Rivera, who said she is invested in both.

“We can work towards long-term systems change, but also acknowledging that in the here and now, this is the reality that exists,” Rivera said. “We need to help folks connect to the resources that are available.”

A pandemic-era fix for digital connectivity goes mainstream

Digital navigators first cropped up during the pandemic when going online became a main source of connection, and quickly landed in Philly after the model was first established.

The National Digital Inclusion Alliance, a nationwide digital equity advocacy organization, first adopted the term “digital navigators” in 2020 and began helping programs across the country introduce the model.

In Philadelphia, the Digital Literacy Alliance, a city-run coalition of online equity stakeholders, took charge of the effort. It chose three organizations in 2020 to receive $30,000 grants to establish digital navigator roles.

At first, it was an experiment.

“We dipped our toe into this water, and were really piloting whether or not this was something that folks needed,” Juliet Fink Yates, broadband and digital inclusion manager for Philly’s Office of Innovation and Technology, told Technical.ly.

Since then, after proving itself to be a useful model, digital navigators have fine-tuned their roles. Now, anyone who is familiar with digital resources, people offering IT support and digital skills trainers could be navigators, depending on what the community needs.

The idea was to partner with trusted organizations who really had the trust of their local communities.

Juliet Fink Yates, broadband and digital inclusion manager for Philly’s Office of Innovation and Technology

The focus has evolved, too, as community needs change. For example, digital navigators turned their attention to the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) in 2023, signing up qualifying families for the federal internet subsidy. But when the ACP ended earlier this year, they pivoted to helping those families transition to other affordable internet options that work for them.

Though it’s not a static role, they all follow the same basic guidelines. Digital navigator organizations have four key responsibilities: connecting people to reliable internet, connecting people to devices, providing digital skills resources and offering one-on-one support for any of the following, according to David Cooper Moore, program lead for TLC.

Partner organizations across Philly help make this happen.

It started with social services org SEAMAAC, Drexel University’s ExCITe Center and adult education nonprofit Beyond Literacy (formerly the Community Learning Center) in 2020. Then, in 2023, additional funding allowed the program to add Hispanic community nonprofit Esperanza as a partner organization.

Beyond city lines, the Southeast Pennsylvania Digital Navigator Network also expanded to Bucks, Chester, Delaware and Montgomery counties in 2023 thanks to a $317,000 grant from Comcast, which continues to fund digital navigator efforts along with the city through the United Way of Greater Philadelphia and Southern New Jersey.

The city sets guidelines for what digital navigators should be doing generally, but the organizations have the autonomy to work with communities the way they think will be most beneficial, Fink Yates said.

“When we designed the program from the get-go, we did not feel like the city knew every community well,” Fink Yates said. “The idea was to partner with trusted organizations who really had the trust of their local communities.”

How does that work in practice?

People in need can call or email those digital navigator organizations directly if they need help. They can also call the city’s 24/7 hotline at 211 to schedule an appointment with a digital navigator.

Once connected, the navigator will talk to each person through their personal needs, whether that’s helping them send an email or getting them signed up for digital skills classes.

There’s a lot of open-ended room for adjustment based on both individual and community needs, which was a key goal in the project’s design.

“It’s really about figuring out where the gaps in particular services and access to particular demographics in the city are,” Moore said. “Then partnering with folks intentionally and expanding one organization at a time.”

Tech support is a gateway to other community support

The work that navigators do is intertwined with systemic digital equity work, largely because it’s already a part of what many of the partner organizations do.

Generally, each digital navigator organization was addressing some form of digital support throughout its social services work, according to Moore. The partnership with the city provides funding to take that work to the next level and provides specific resources for internet and device access.

And offering that additional resource keeps residents coming back for other types of support.

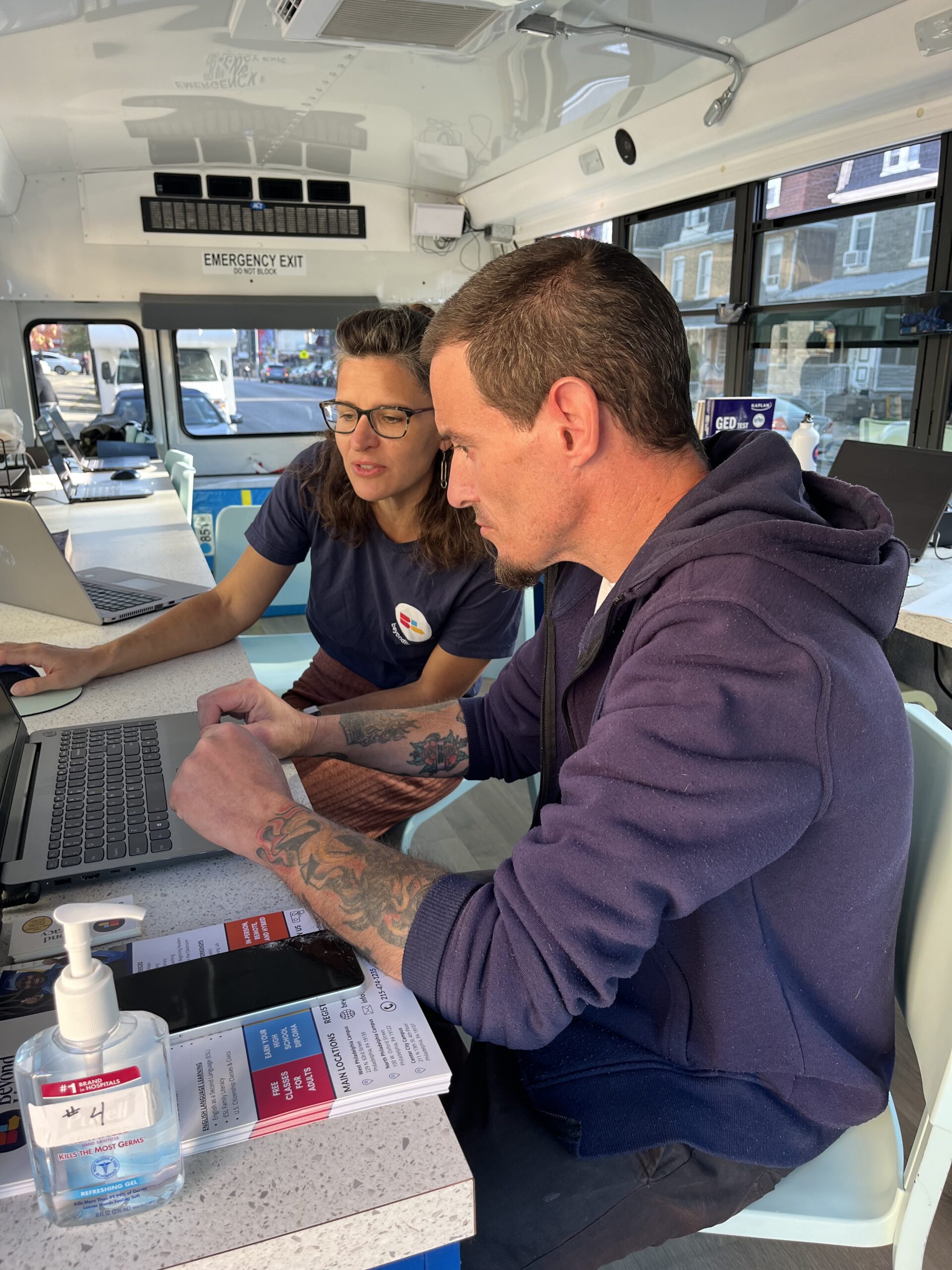

For example, Beyond Literacy always included some level of digital skills training in its programming because digital skills are a workforce skill, Kieran Farrell, director of student support and digital navigation programs at the organization, said. When the pandemic hit, it started offering device access and one-on-one support to meet that need, she said.

That made it a natural fit for the digital navigators program and now people who come to Beyond Literacy for its adult literacy programming may also see it as a trusted source for digital help and vice versa.

“We’re transitioning from a one-off, here’s a support service, to a mainstay in the community, like a long-standing, trusted resource,” Farrell said.

Kevin Young, a digital navigator at Drexel University’s ExCITe Center, shared a real-life example of how the program can engage the surrounding community.

Drexel University’s digital navigator program primarily focuses on the West Philadelphia Promise Neighborhood, a career opportunity initiative funded by the US Department of Education. People often come to them for digital skills help or tech support, but then they keep coming back to use the computer lab, sign up for classes or take advantage of health screenings.

One resident came to the digital navigators after being released from prison to catch up on tech literacy. After learning those skills, however, he was motivated to get his GED and pursue his commercial driver’s license, according to Young.

“Once they trust you and trust all that’s going on around them, once they get into the center, get on that campus, then they begin to look for other services,” Young said. “They’re open to the information that’s being given to them.”

Across partner organizations, however, there aren’t always enough navigators to help people who request it.

Because SEAMAAC provides digital help to almost everyone who comes to the org, Kahina Guenfoud, adult literacy and digital access coordinator at SEAMAAC, said there are limited resources or time to assist everyone who needs it. Sometimes, she tries to refer people to the other partners, but people are hesitant.

The digital navigator model is built on community trust, and clients have a hard time trusting people they don’t know, she said.

Still, they’re trying to close that gap to build more trust across organizations by referring residents and swapping ideas.

For example, TLC hosts a biweekly meeting for the digital navigator organizations to build community, share resources and discuss common challenges. They recently found success connecting each other to resources like PCs for People, a device refurbishment and distribution program that expanded to Philly in 2023.

One-on-one help won’t go away, even with more systemic change

Community orgs and advocates agree that digital navigators are a resource the city should continue funding, but they also insist that systemic change is still needed.

Digital access barriers usually relate to availability, affordability and adoption, according to a report from Boston Consulting Group. Digital navigators address the adoption arm of this issue, but they’re most effective when heavily invested in, the report said.

Across Philly and Pennsylvania alike, there have been more funds to support digital equity, including the navigator program.

The Digital Equity Act dedicates $2.75 billion in federal funds to promote digital equity and inclusion work. The city submitted a grant application to support the digital navigators program and Drexel University submitted one related to workforce development and digital navigators, according to Andy Stutzman, executive director of digital equity advocate Next Century Cities and former leader of Drexel’s digital navigator program.

You’re always going to need organizations that are filled with people who care about the mission and care about the individual successes.

Kieran Farrell, director of student support and digital navigation programs at Beyond Literacy

The results of those applications aren’t in yet, but other funding programs support device distribution and public access to the internet in the city. Additionally, the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment program will contribute $1.16 billion in funds to expanding internet infrastructure across the state.

So, digital navigators don’t erase or distract from that work to increase digital equity-focused funding and programs, Rivera of TLC said. They simply do their part to step up for individualized support in the meantime.

Plus, there will always be new technology that people need help to understand, Farrell of Beyond Literacy said. And it all comes back to individualized aid to help the community adjust, even if a larger stride toward digital equity gets put in place.

“You’re always going to need organizations that are filled with people who care about the mission and care about the individual successes,” Farrell said. “And making those one-on-one connections.”

Sarah Huffman is a 2022-2024 corps member for Report for America, an initiative of The Groundtruth Project that pairs young journalists with local newsrooms. This position is supported by the Lenfest Institute for Journalism.