When the Moon is waxing, it shines in the evening and grows wider each night — as the terminator (the line that divides night and day on the lunar surface) unveils more and more of the blasted, alien landscape.

Gary Seronik

Maybe you just got a shiny new telescope to call your own. Congratulations — you could be on your way to making lifelong friends with stupendous, faraway things in the dark over your roof every night, things you never knew were floating right there waiting for you all along.

However, most of them are so far and faint that just finding and identifying them is the challenge — and the accomplishment! Whether your new scope is a long, sleek tube or a compact marvel of computerized wizardry, surely you’re itching to try it out.

Before You Observe

Here are three essential tips for starting on the right foot, to avoid frustrations and dead ends and to move quickly up the learning curve.

First, get your scope all set up indoors. Read the instructions, and get to know how everything works — how the telescope moves and (maybe) can be locked in place, how to change eyepieces, how to align or “collimate” the optical parts if this is necessary, and so on — in warmth and comfort. That way you won’t have to figure out unfamiliar knobs, settings, and adjustments outside in the cold and dark.

Second, take the scope outside in the daytime and familiarize yourself with how it works on distant scenes — treetops, buildings — to get a good feel for what it actually does. Don’t be surprised if the view is upside down. Allowing this keeps the optical parts nice and simple, meaning clearer and less trouble prone. And it doesn’t matter because there’s no up or down in space!

You’ll quickly find that the telescope’s lowest magnification (the eyepiece with the longest focal length; the one with the largest lenses and the highest number of “mm” printed on it) gives the brightest, sharpest, and widest views. And, with the least wiggles. The lowest power also makes it easiest to find what you’re trying to aim at, thanks to that relatively wide field of view. So you’ll always want to start off with the lowest power. Switch to a higher-magnification eyepiece only after you’ve found your target, got it centered, and had a good, careful first look.

If the telescope has a little finderscope or a red-dot pointing device attached to its side, daytime is the easiest time to align the finder with the main scope. You really need to do this! Aim the telescope at a distant treetop or other landmark and center it in the main view. Lock the mount’s motions if the mount allows this. Recheck that the treetop is still centered, then look through the finderscope. Use the finder’s adjustment screws to center its crosshairs (or red dot) on the same treetop. Then recheck again that it’s still in the center of the main scope’s view, in case you bumped it off in the process.

Third, plan to be patient. Spend time with each sky object you’re able to locate, and really get to know it. Too many first-time telescope users unconsciously expect something like Hubble-like brightness and color in the eyepiece — when in fact most astronomical objects are very dim to the human eye. Moreover, our night vision sees dim things mostly as shades of gray, not in color. Much of what the universe has to offer is subtle and, again, extremely far away!

But the longer and more carefully you examine something faint and difficult, the more of it you’ll gradually discern. Astronomy teaches patience. Learn it.

On the other hand, the Moon and the naked-eye planets are bright and easy to find. They make excellent first targets for new telescopic observers. Sky & Telescope‘s This Week’s Sky at a Glance has suggestions for both telescopic and naked-eye viewing of the brightest stars and planets. For instance, here’s looking east as the stars come out in late December 2024:

New-Telescope Delight: The Moon

The Moon is one celestial object that never fails to impress in even the most humble scope. It’s our nearest neighbor in space — big, bright, starkly bleak, and a mere quarter million miles away. That’s a hundred times closer than the nearest planet ever gets. An amateur telescope and a detailed Moon map can keep you busy forever.

Tonight (December 25, 2024) the Moon is gone from the evening sky; it’s a waning crescent that rises in the early-morning hours and hangs in the eastern dawn. It will return to evening view around New Year’s Day as a crescent in the western twilight, then it will grow to closely match the photo above on January 5, 2025.

As that photo suggests, lunar surface features show best when they are near the Moon’s terminator, the lunar sunrise or sunset line. There, the low Sun in the Moon’s sky makes even low landforms cast long, stark black shadows and stand out dramatically. The advancing terminator unveils new landscapes day by day when the Moon is waxing before full, then hides them in darkness day by day when the Moon is waning after full.

In between at full Moon, the terminator lies all around the Moon’s edge essentially out of sight. So full phase (which will next come on January 13th) is actually the worst time to see detail on the Moon! That’s because its whole face is brightly sunlit by the Sun directly behind us, so the lunar mountains, hills, craters and cliffs will cast no shadows to reveal them as other than flat. Everything will just be shades of brilliant gray-white. Still, don’t ignore the full Moon! Now you get a complete look at the flat, gray lunar plains or “seas”; the maria in Latin. Brighter areas are more mountainous, and many craters large and small will reveal themselves at full Moon by their bright white rims.

Bright Planets

Four bright planets await you now in the evening sky: Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

Venus is the brightest planet and the first to show as twilight fades. It’s that bright “Evening Star” fairly high in the southwest in twilight, and lower after dark. Venus is covered in white clouds that are brilliantly lit by sunlight twice as bright as sunlight on Earth. In a telescope Venus shows phases like the Moon, but they change more slowly. Right now Venus appears slightly gibbous: just a bit more than half lit. In January and February Venus will wane in phase to a thick crescent while enlarging in your cope as it swings closer to Earth. In March Venus will become an almost shockingly thin crescent before plunging down out of sight into the sunset.

Saturn now shines higher to Venus’s upper left, by about two fist-widths when you hold your fist at arm’s length. It’s much less bright than Venus, but there are no stars in the area nearly as bright to confuse it with. A telescope reveals that this year, we see Saturn’s iconic rings very close to edge on. They look at first look like a toothpick stuck through a cheese ball. We get this view of Saturn only every 15 years. Watch carefully to see if you can make out further detail in the rings. And can you see hints of banding on Saturn’s globe itself?

Saturn has multiple moons. The biggest, Titan, is detectable in a 3-inch or larger telescope as a tiny pinpoint in Saturn’s viscinity. Tonight (December 25th) it’s to one side of Saturn by almost five times the length of the rings, in line with the rings. Can you detect Titan’s slightly orange tint? You are looking at its smoggy methane atmosphere.

And, watch very carefully to see if you can discern any of Saturn’s fainter moons closer in.

Saturn and Venus draw closer together for the next three weeks. They’ll pass each other on January 18th, when they’ll be separated by hardly more than the width of your finger at arm’s length.

Now turn and look high in the southeast. Jupiter is the brilliant white dot there. It’s second in brightness only to Venus.

Even the smallest telescope at low power will show Jupiter’s four pointlike moons on either side of it. They change configuration endlessly from night to night as they orbit the planet. This evening, December 25th, you’ll find Io and Europa on one side of Jupiter, Ganymede (the brightest) farther on Jupiter’s other side, and Callisto (the faintest) out past Ganymede. Tomorrow their configuration will be quite different, and on and on while Jupiter is in view all winter and early spring. They’ve been at it up there every night for 4.6 billion years, ever since the solar system formed.

Now switch to fairly high power. Jupiter itself spins so fast (once every 10 hours) that it’s not quite round, as a small scope will reveal.

And can you make out any of Jupiter’s parallel tan cloud belts? They may darken or brighten, broaden or narrow, over a matter of months or years. They won’t exactly leap out at you. Keep looking, and looking. Carefully. You may catch an occasional moment of steady air when the planet sharpens up. The “atmospheric seeing,” as it’s called, changes from blurrier to sharper from night to night and sometimes from moment to moment.

There’s another reason to keep looking. When you’re working near the limit of your vision, as you usually will be in astronomy, it takes time and continued attention to see all that you can see. Things that were at first invisible may start to occasionally flicker into view, then become definite enough to hold almost steadily. Did we say astronomy teaches patience?

Jupiter’s famous Great Red Spot, in the edge of the South Equatorial Belt, is a harder catch. It may need at least a 6-inch scope and a night of especially steady seeing. The Red Spot is currently very pale orange (it too changes), and it has been gradually shrinking for decades. And, of course, it needs to be on the side of Jupiter facing Earth at the time when you look!

Mars rises to shine bright fiery orange in the east as evening grows late. It appears smaller than the planets above. Nevertheless it is closer and larger now through January than we will see it for the next two years. You’re just in time.

By 11 p.m. Mars will be high enough in the east that you’re seeing it through relatively thin air, meaning that in a telescope it will appear less shimmery and fuzzed up by the poor atmospheric “seeing” lower down. Can you make out Mars’s bright North Polar Cap and perhaps some of its subtle dark markings?

Little Mercury, the last bright planet, is now low in the southeast during dawn, in the bad atmospheric seeing low down as well as in the growing light of the oncoming day. Its best evening showing this year will be in early March.

Deeper Telescopic Sights

Of course there’s much more to the night sky than the Moon and planets! Winter nights often bring crisp, transparent skies with a grand canopy of stars. But with so many inviting targets overhead, where to point first?

Well, upper left of Jupiter by a bit more than a fist at arm’s length is the Pleiades star cluster. It’s visible to the naked eye as a little misty patch about the size of your fingertip at arm’s length. Most people can make out the six brightest Pleiades stars with the unaided eye (and distance glasses if necessary). They form a tiny dipper shape. But a telescope will show a whole swarm, including a few double stars, and the dipper pattern will look huge and bright — even overspilling your eyepiece view at all but the very lowest magnifications.

Astronomers have determined that the Pleiades include more than 500 stars in all. Like other star clusters, the Pleiades are held together by their mutual gravity. They swarm like bees on a timescale of millions of years. This one is classed as an open cluster for the stars’ relatively uncrowded arrangement. It’s nearby as star clusters go, traveling through space as a swarm about 440 light-years away.

The Pleiades stars, astronomers have determined, began to shine only about 80 million years ago. This makes them mere toddlers compared to our Sun and solar system, age 4.6 billion years. These youthful suns are astonishingly energetic. Alcyone (al-SIGH-oh-nee), the brightest, is at least 350 times as luminous as our Sun. Like the other bright Pleiads it gleams with an intense bluish-white light — a sign that it’s unusually hot and massive.

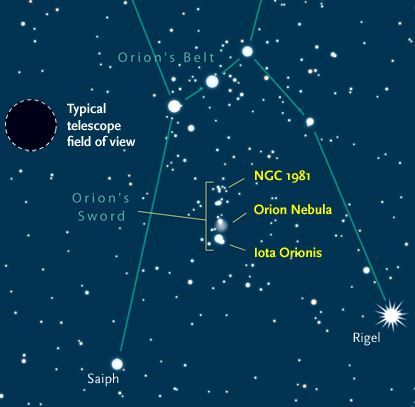

Next, here’s a deeper suggestion. The familiar constellation Orion climbs the southeastern sky after dinnertime at this season of year. In its middle, look for the three-star line of Orion’s Belt. The Belt is now almost vertical in early evening. It turns diagonal (as shown below) when Orion is higher later at night.

Sky & Telescope diagram

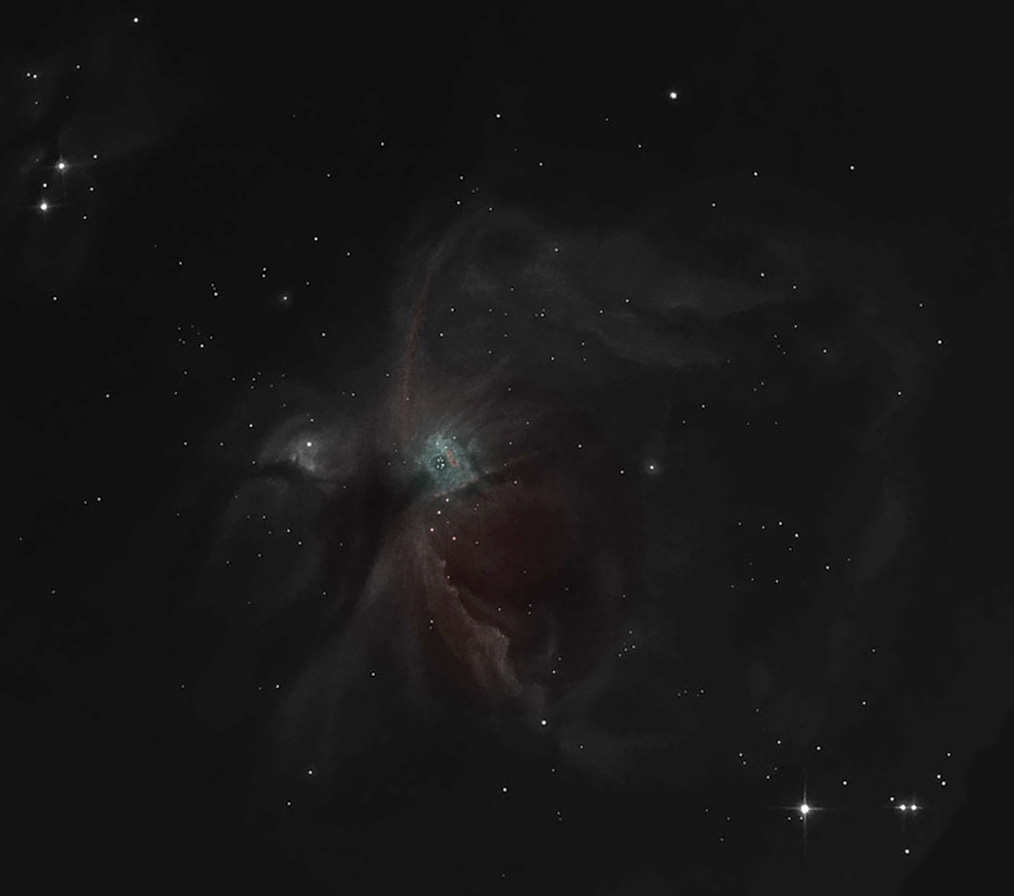

Just a few degrees south of the Belt, in other words a few finger-widths at arm’s length, runs a smaller, dimmer line of stars: Orion’s Sword. Within it lies the Orion Nebula, a luminous cloud of gas and dust where new stars are forming by the hundreds. It shows pink in many photographs, but to the human eye it’s dim gray with a hint of green. The nebula is evident in any telescope once you get pointed at it, and so is the tight quartet of young stars near its center, known as the Trapezium. Astronomers refer to the Orion Nebula as Messier 42 (M42), and you’ll see it labeled that way on star charts. Located about 1,400 light-years away, it’s the closest massive star-forming nebula to Earth.

Dim objects like nebulae are best seen when the sky is moonless and really dark. The farther you can get out from under the skyglow of city light pollution, the better. But don’t let moonlight or light pollution dissuade you from finding what you can see from your own backyard or apartment balcony or roof garden or fire escape! Choose reasonably bright targets to hunt, and develop the skills to find them and observe them carefully so you’ll be ready to make the most of better conditions when the chance arises. For instance, the sky may be especially clean and dark the night after a storm passes through.

Howard Banich / S&T Online Gallery

Joshua Rhoades / S&T Online Gallery

Next Steps in Astronomy

To find much else in the night sky, start learning the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope — the same way that on a globe of Earth, you need to know the continents and countries before you can pinpoint, say, Milan or Odesa or Jakarta.

For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy (ahem).

You’ll also want a good, detailed star atlas (set of more detailed maps), such as the widely used Pocket Sky Atlas; a good deep-sky guidebook; and some practice in how to use the maps to pinpoint the aim of your telescope onto something too faint to see with your eyes alone. So be sure to read our article How To Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

For more tips on skywatching and how to get the most out of your scope, see this website’s Observing section and Getting Started section.

Whatever else, stick with it. Nobody is born knowing this stuff. Work your way into the hobby at your own pace, finding things to know and do and understand without worrying about everything else you haven’t got to yet. That’s kinda the way like is in a big universe, right?